Just how close are we to losing one of Africa’s greatest fashion treasures? And what will it take to reclaim it? Why are we letting machine looms erase centuries of memory? Why are the original weavers being forgotten, underpaid, and unseen? And most importantly, can Aṣọ-Oke survive the global fashion race?

The 2025 Met Gala theme, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style”, may have given Aṣọ-Oke its most glamorous stage yet, stitched into Deji & Kola’s sharply cut tuxedos and draped across red carpet shoulders in defiant elegance. But while the world applauded its sheen and symbolism, few paused to ask: who still weaves it by hand?

Olamide Latifat Mohammed, founder and creative director of Bolamsasooke, is one of the few sounding that alarm. Her brand doesn’t merely preserve Yoruba textile traditions—it dares to reimagine them. Born into a matrilineal heritage of loom masters and market women, Olamide stands at the intersection of ancestry and innovation. In a time when Aṣọ-Oke is often reduced to a stylistic prop or reproduced by machines for speed and scale, she insists on honouring its soul.

In this timely conversation, Olamide peels back the fabric, literally and metaphorically. She speaks about the quiet violence of cultural erasure, the undervaluation of indigenous artisans, and why fashion must become more than commerce. It must become memory.

FAB: When you think of your earliest memory of Aṣọ-Oke, what comes to mind? Is it the loom, the colours, or your grandmother’s home?

Olamide Latifat: Honestly, it’s the colours. As kids, we’re naturally curious, and colour is one of the first things that grabs our attention. Growing up, I saw all kinds of vibrant combinations. Our home had a backyard where several women gathered to weave. My mum wasn’t a weaver herself, but she ran a business selling what they produced. She was always the one coordinating everything.

From a young age, we understood the business side of things, but for me, it was the colours that stood out. I remember how different women would come with various threads and weave them into beautiful patterns. That, I think, was my earliest introduction to colour and why I became so drawn to it.

Why Aṣọ-Oke Still Matters in Global Fashion

FAB: That’s interesting. And as an adult, you’ve described Aṣọ-Oke as more than just fabric. So, at what point did you realize it was also an identity?

Olamide Latifat: Thank you. I began to understand Aṣọ-Oke as an identity when I noticed how central it was to every important Nigerian event. It doesn’t matter the occasion—naming ceremonies, weddings, chieftaincy titles—Aṣọ-Oke is always there. It’s not just fabric; it symbolizes dignity, pride, and belonging.

After university, I was still trying to find my path. I’m naturally curious, and even though I studied Computer Science and earned cybersecurity certifications, something shifted when I worked with Bukhara Africa around 2012 or 2013. They came to Nigeria for the XL Touching Lives project and needed vibrant African fabrics for the studio. Without hesitation, I suggested Aṣọ-Oke.

There’s something about it, it’s celebratory, it’s rooted. When someone says, “I’m using Aṣọ-Oke for my baby’s naming ceremony,” it immediately suggests class, culture, and heritage. Even back then, we had no idea Aṣọ-Oke would gain global recognition the way it has. Today, designers all over the world are incorporating it into their work, many without fully understanding its origins.

But what really defines it as an identity is the weaving itself. You don’t see just anyone weaving Aṣọ-Oke. And by that, I mean you don’t find random people deciding to pick it up casually. Most are in the business of selling it, not making it. The people who do weave it carry the heritage. They understand the meaning, the story; it’s in their hands, quite literally.

I recently posted a video about this. I visit my weavers in Agege weekly. We chat, bring them gifts, and check on our orders, but none of us ever sits at the loom. Why? Because we see weaving as their identity. They know what each thread represents. We just see the final product, a beautiful fabric.

One day, I decided to try it. My head weaver joked, “Aunty, so you want to be like us today? Let’s see how long you last!” Honestly, those five minutes felt like forever. I was sweating, my back ached, and my hands were sore. Meanwhile, they do this joyfully, day in, day out. That’s identity. It lives in the hands of those who create from a place of legacy, not just commerce.

FAB: Let me take you further into that idea of identity. I’m Yoruba myself, and I know we have Aṣọ-Oke from Iseyin, from Ondo, and even from Benue State. I’ve felt the differences in texture and colour; you can often tell if someone is Tiv or Idoma just by their Aṣọ-Oke. So, what’s the story behind these variations?

Olamide Latifat: Let me take you back to the roots of Aṣọ-Oke. Do you know why it’s called that? The name comes from “Ara Ilu Oke”, which means “people from the uplands” in Yoruba. The fabric was traditionally woven by these upland communities. In English, you could loosely translate Aṣọ-Oke to mean “Top Cloth”, with aṣọ meaning cloth and oke meaning upland or top.

So, Aṣọ-Oke refers specifically to the cloth woven by people in the upper southwestern region of Nigeria. Beneath that region geographically, you’ll find groups like the Iseyin, Ibadan, and Kabba. The Kabba people, for example, are from Kogi State and are often identified with the Ebira language and culture. To reach trading hubs like Iseyin, Ibadan, or Ede, they would typically pass through Ondo.

Now, there’s a traditional market held every 15 days between Ibadan and Osun. Communities from Kabba, Ondo, and surrounding areas gather there to trade Aṣọ-Oke. The Kabba people would bring their large, heavy cotton weaves—often in black-and-white or red-and-black stripes—to sell in Ede or at the Oje Market in Ibadan.

Meanwhile, the Ondo people are known for a different style called Alari, a magenta or wine-coloured fabric with distinctive line patterns. These colour and texture choices became part of how each group expressed its identity. As demand grew, people began asking themselves, “How do we set our fabric apart?” So, they created unique colour combinations and patterns. These decisions were often made right there in the markets, during trade or casual conversations about emerging trends.

Let’s talk about Sanyan, another type of Aṣọ-Oke. It’s a light brown or “carton” colour, made of 100% cotton with white lines running through. Reserved mostly for royalty and chieftaincy titles, it’s a highly esteemed textile. So beyond colour and texture, social significance also plays a role.

Even the size of the fabric tells a story. Men traditionally weave Awe, the narrow strips used for Agbada. That style is more common among the Ondo. But the women—particularly from Kabba and Ebira communities—are known for weaving Mùmùmùmù, the much wider pieces that span three-and-a-half yards in a single stretch.

The Ondo fabrics usually feature structured, linear designs, while others are more expansive and bold. To truly understand Aṣọ-Oke, you have to trace where each thread of history and identity intersects. Only then can you appreciate what makes each one unique.

FAB: Thank you for that powerful history lesson. You’ve touched on something else, class. For example, Sanyan is traditionally considered royal fabric. But these days, the lines seem blurred. Should we still maintain those class distinctions, that certain fabrics are meant for royalty or specific social groups?

Olamide Latifat: That’s such an important question. What we’re seeing now is the influence of global trends. Everyone’s turning their eyes toward Africa for our fashion, our colours, and our styling. And now, we’re finally starting to value it ourselves.

It’s funny, someone buys an Aṣọ-Oke jacket for $5,000 at New York Fashion Week, and suddenly we’re like, “Wait, is that the same Aṣọ-Oke we’ve always had here in Nigeria?” We didn’t see its value until others began presenting it as luxury. That’s the shift happening now.

Take last year’s Ojude Oba celebration. The colours, the opulence, the cultural pride—it was breathtaking. People showed up dressed in coordinated Aṣọ-Oke outfits, showcasing not just tradition but identity. And now we’re seeing that spirit spread. Look at what’s happening with the Lisabi festival; it’s becoming another cultural showcase, just like Ojude Oba.

From what we’ve supplied for this year’s Ojude Oba, I can tell you it’s going to be massive. And the beauty of it? Many people participating don’t even fully understand the origins of Ojude Oba. They’re simply drawn in by the colours, the elegance, and the viral photos of people dressed in traditional attire. Folks from all over the world are buying these fabrics, not necessarily because of the history, but because of how bold and beautiful they are. That right there, that’s the power of identity.

FAB: Following up on Ojude Oba—and this is just an aside—is it even possible to have Ojude Oba without Aṣọ-Oke?

Olamide Latifat: Absolutely not.

FAB: So, what is the cultural weight of Aṣọ-Oke in Ojude Oba?

Olamide Latifat: My dad has participated in Ojude Oba celebrations since I was a child. Each club involved in the festival selects a specific fabric in preparation, and it’s always Aṣọ-Oke. Wearing it is symbolic. It’s how we say, “We made it this year.” Let me put it another way: it’s a way of saying, “We returned home to celebrate.” Ojude Oba isn’t just for residents of Ijebu; people travel from all over Nigeria and even abroad to be part of it.

That’s why it happens on the third day after Ileya (Eid al-Adha). During Ileya, families gather back home, and by the third day, everyone comes together in front of the king’s palace to celebrate with him; that’s the heart of Ojude Oba. And to present a strong, united image in such a public setting, everyone dresses in coordinated Aṣọ-Oke. It symbolizes family pride, continuity, and the joy of being alive. Each family or club chooses their unique colour combination, which becomes a marker of identity.

FAB: Let’s dive into the different types of Aṣọ-Oke. You briefly mentioned Sanyan and Alari, but let’s go deeper. We have Alari, Sanyan, Jawu… and now, contemporary styles are emerging. I’m even seeing metallic Sanyan. People are mixing in silk too.

Olamide Latifat: Yes, let’s start with Alari. It’s usually identified by its deep, bold colours—think wine, burgundy, magenta, or deep red—interwoven with contrasting stripes, often green, white, or another light hue to break up the intensity. Traditionally, Alari is associated with royalty. That’s why it’s often called Alari Baba Aṣọ-Oke. It’s a prestigious choice, commonly worn at high-profile weddings. You know the kind of old-school elegance where, just by looking at someone’s attire, you could tell they belonged to wealth or royalty? That’s what Alari represented. The Okoya family, for instance, wore clothes that spoke status without words.

Sanyan, on the other hand, comes in softer tones like beige, champagne, or light brown, shades that are closely related. Historically, it was woven from silk or cotton, though today it’s being reimagined with metallic threads. Sanyan is especially popular for weddings. The Ilorin people, for example, are known for their love of Sanyan. Ilorin has a rich Aṣọ-Oke weaving heritage too. There’s a group called Agboli Alashọ known for their craft. In Kwara State and Ilorin, most weddings still feature the traditional cotton or silk Sanyan, while we Yorubas tend to experiment more with colours and materials.

Then there’s Etu, typically deep navy or dark blue with light blue or sky-blue stripes. It’s traditionally worn by men, probably because of the colour. It carries a sense of maturity, masculinity, and understated elegance.

Now, let’s talk about modern Aṣọ-Oke, especially the metallic types. Back in the day, we used to weave cotton and add just a touch of lurex—a shiny, metallic thread—for a subtle shimmer. My mum used to call it Oju to n Sọro (meaning, “eye that speaks”). We never made the entire fabric shiny, just sprinkled in enough to catch the light.

But as fashion evolved—and you know how much we love to stand out—the mindset shifted. People began asking, “What if I want to shine completely?” That’s when we started weaving full-metallic Aṣọ-Oke entirely with lurex. It became the go-to for bridal wear: “I want to shine on my big day!” Today, we even combine two lurex colours in one weave, what we call double-woven or double-tone. That’s how you get that reflective, luxurious look with two shimmering shades dancing together in the fabric. You can’t achieve that with plain cotton. It’s a modern fusion where tradition meets innovation, and the result is elegance, sparkle, and cultural pride.

FAB: You just mentioned combining two lurex threads. On average, how long does it take to weave a single piece of authentic Aṣọ-Oke?

Olamide Latifat: When you say “authentic”, are you referring to cotton?

FAB: Yes, pure cotton.

Olamide Latifat: Then it usually takes about three weeks to complete a full bridal Aṣọ-Oke made from cotton. Each day, the weaver returns to her loom and spends hours weaving. A bridal set typically includes five yards of fabric, along with the ipele and gele. And by bridal, I mean the large, loom-woven Aṣọ-Oke—not the narrow stripe versions. Back in the day, people used to buy stripe-patterned Aṣọ-Oke and join the pieces. But today, because we want to make a statement and show affluence, many prefer seamless, loom-woven pieces. This premium look can only be produced by highly skilled weavers.

Fighting Machine-Made Erasure with Handwoven Truth

FAB: Three weeks! That’s intense. But now, we have machine-made versions, synthetic Aṣọ-Oke. I’ve received a few for events, and my first thought was, this feels so light. So how are artisans—who spend three painstaking weeks crafting something deeply cultural—meant to compete with that? Especially when buyers complain about the price?

Olamide Latifat: I’m glad you mentioned how light it feels. That’s one of the major differences between machine-woven and handwoven. Aṣọ-Oke, texture and authenticity. Handwoven Aṣọ-Oke has soul. There’s a connection to it. Let me break it down.

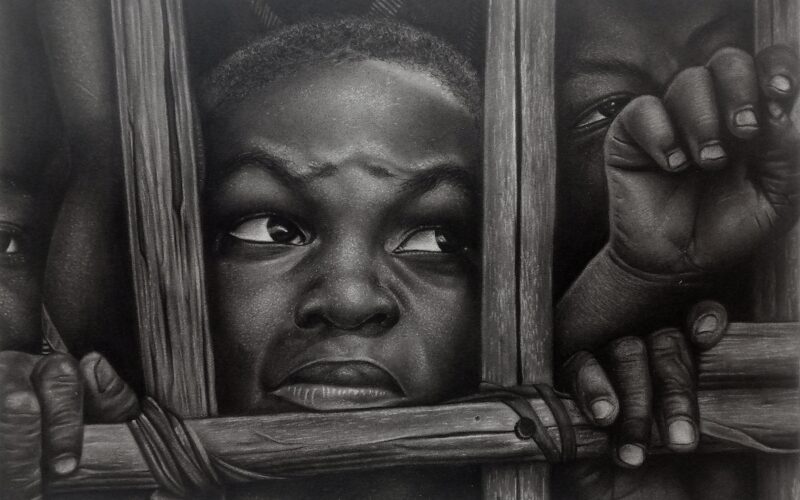

Handwoven Aṣọ-Oke is made entirely by hand. That’s why it takes so long. I once sat down to weave for just five minutes, and my back ached. That wasn’t for content; it was real. When I posted the video, I could’ve used a trending song and made it aesthetic. But I chose to show the reality, the physical toll this work takes on the artisans, the invisible hands behind the fabric.

Handwoven Aṣọ-Oke is thicker, richer in texture, and more detailed. Here’s what my weaver told me that day. I was learning how to pass the loom thread, and I should explain this process briefly.

The fabric is crafted on a narrow loom. Each thread is manually tied to a loom stick, then passed through, one after the other. Imagine guiding a single, delicate thread to the right, pulling it back, then guiding it to the left. You repeat this over and over again. To complete just one fabric, you might pass a thread millions of times. That’s not an exaggeration. The standard Aṣọ-Oke length is 90 inches, and each weft thread is far less than an inch wide. Just imagine how many passes that takes. And as you weave, you have to beat the loom hard with your hands to tighten the fabric so it doesn’t unravel.

Now contrast that with machine-woven fabric. It may look shiny and attractive, but it lacks that depth and connection. Machines don’t feel the strain, the sweat, or the stories. But a handweaver does. Modernization is good, I understand; we want speed and convenience. But in an article I wrote recently, I asked a serious question: Is this craft dying?

Here’s my analysis. When I was a child, my mum never wanted me to become a weaver. Why? Because of the hardship. That same hardship I felt after just five minutes on the loom. Now imagine sitting through it every day for three weeks, just to make one bridal outfit. And then what do you hear? “It’s too expensive.” Because people don’t consider the labour, the pain, the craftsmanship behind it. The mindset is, “It’s just local fabric; why should it cost more?”

No one pays for the emotion behind the weave. That’s why it hurts when people compare it to machine-made versions. The artisans are ageing, many are dying, and they’re not passing the skill to their children. So, yes, the craft is truly at risk.

The Crisis Facing Indigenous Nigerian Weavers

FAB: Yes. It’s really emotional. I remember growing up; I used to see them in the neighbourhood. Honestly, we saw them as poor people. It seemed like they had no other options. They would show up daily to weave yet barely got paid for their work. Like you rightly said, no parent wants their child to end up in that situation. So how do we ensure fair and ethical payment for these weavers? Because if this knowledge dies—like many other aspects of our culture already have—we’ll be left with nothing.

Olamide Latifat: That’s the question we all keep asking. I believe it requires a mix of community support and ethical business practices. That’s really the core of it. I try not to place the responsibility solely on the government. They already have so much on their plate—many of which they aren’t even handling—let alone seeing or supporting the unseen, invisible people behind this craft. But when people buy a finished piece, they don’t see the labour behind it. They just see a beautiful cloth. Yet this fabric could be empowering many artisans if we truly valued it.

Even I struggle with what “empowerment” should look like. And no, it doesn’t just mean giving them money. If you give them a lump sum, many will simply leave to start something less stressful, because let’s be honest, this work is hard. Maybe the answer is to pay them more, as we try to do. But at the same time, businesses have to stay afloat. We can’t pay more than we can sell.

Perhaps we should begin highlighting the weavers on social media, showing the people behind the craft, if they’re willing. I’ve had weavers say, “Aunty, please don’t put me on camera.” Some prefer to stay private. Still, giving them a face and a voice could make a difference.

Another idea is to support and sponsor young apprentices. But who’s even interested these days? Who wakes up and says, “Aunty, I want to learn how to weave”? That’s why we need to change the narrative. We must stop comparing machine-made Aṣọ-Oke with handwoven ones. Aṣọ-Oke is heritage. It is handwoven in Nigeria by Yoruba artisans.

Yes, other African cultures have their woven textiles, like Ghana’s Kente. It’s also handwoven. But this is what I know, and we need to tell the story behind it. We need to keep emphasizing its authenticity, not dilute it with machine alternatives.

Why Many Young Artisans Are Leaving the Loom

FAB: How do you think Nigerian institutions could step in? I doubt Aṣọ-Oke is the only traditional craft at risk. Could there be a way to integrate it into educational curricula or repackage it to appeal to young people? Like how Idris Olabode (Clay of Lagos) has made pottery and ceramics cool again.

Olamide Latifat: You’re absolutely right. With Aṣọ-Oke, I don’t want to start naming institutions so it doesn’t seem like I’m offloading responsibility onto people who might not even understand the culture. I always say it’s my responsibility too.

That said, a lot of young Nigerians today are focused on quick money. So maybe the place to start is in schools, make weaving seem fun and worthwhile, and then we might attract the few who are genuinely interested.

One idea we’re exploring is this: what if we support the weavers’ children by sending them to school while also encouraging them to learn weaving alongside their studies? That way, they get an education and still connect with the craft.

But we also have to respect choice. Just because someone is sponsored doesn’t mean they owe us weaving for life. It’s their decision. Even if they’re paid, it’s still a choice. That’s the balance we need to maintain.

FAB: That’s so true. Your mother and grandmother seem to play powerful roles in your story. What’s one lesson they taught you, whether through fabric or life, that continues to guide your work today?

Olamide Latifat: Empowerment, specifically women’s empowerment. I learned that from them because they were empowered women. I remember when I told my mum I wanted to start selling Aṣọ-Oke. She laughed and said, “You can’t do it. It’ll stress you. The weavers will fall sick…” And she wasn’t wrong.

You know, some of the weavers I work with today are children of the women who wove for my grandma. There’s a chain. One of my elderly weavers, Mr Razaq, his father used to weave for my grandma, then he wove for my mum, and now for me. But sadly, he doesn’t have a male child. Maybe if he did, the tradition would continue. That’s the crack; there’s a gap forming in the generational chain.

Still, I keep coming back to empowerment. Empower women. It’s something my mother and grandmother embodied, and it continues to shape everything I do.

Recommended For You

Told Art Was a Waste of Time — Ibrahim Quyum, 21, Now Paints the Future of African Creativity

FAB: From your own sojourn, what’s the most unforgettable thing you’ve experienced or learned in the markets of Ibadan (Oje) or Osun? Any memorable moments?

Olamide Latifat: I learned the power of business relationships. I’ve already told you about the chain, how it all connects. I’m talking about a time before phones, when you couldn’t call ahead and say, “Hey, I’ll be at the market in 15 days.” These were the 7-day or 15-day interval markets, like Oje in Ibadan and Ede in Osun. There was no advance notice, yet each time we arrived, the traders were there at their stalls, ready. That’s where creativity blossomed, where one weaver would proudly unveil a new design to another. Patterns, colours, heritage… it all came to life there. That’s where I learned the business, from my grandmother and my mother. But more importantly, I learned that relationships—real, human connections—are everything.

What’s Next for Aṣọ-Oke and Bolamsasooke

FAB: If you had to take someone on a first date with Aṣọ-Oke, where would you take them? To the market, the loom, or the runway?

Olamide Latifat: Definitely the loom. You can’t build something meaningful if your partner doesn’t understand where your struggle begins. When a client calls and asks, “Why isn’t my Aṣọ-Oke ready?”, and I explain what’s happening with the weavers, you, as my partner, need to understand the weight of that moment. I’m not someone who says, “That’s not my concern; they’re the weavers.” No. I care deeply about their wellbeing. Their emotions, their strength— it’s all woven into the fabric. And so are mine.

FAB: Hmm. When you see Aṣọ-Oke on a runway or a bride, what goes through your mind in that moment?

Olamide Latifat: I see emotion. Others see a beautiful fabric. But as a designer, I see the invisible hands behind it, a woman whose name most people will never know. Her heart is in every thread.

FAB: If you could collaborate with any global designer to reinvent Aṣọ-Oke for the world, who would you choose?

Olamide Latifat: That’s a big question. Honestly, I dream of opening a store in New York. So who would I love to work with? Maybe Christopher John Rogers… or Pierpaolo Piccioli.

FAB: Why them?

Olamide Latifat: Because they both understand storytelling through fashion. Pierpaolo Piccioli brings emotion, softness, and drama, elements that mirror what we do with Aṣọ-Oke weaving. His work moves people. Christopher John Rogers, on the other hand, is bold, especially with colour. And Aṣọ-Oke can be incredibly bold and vibrant. It’s a perfect match. Together, we could translate Yoruba culture onto the global runway.

FAB: As we wrap up, we’ve talked a lot about how this craft is fading. But let’s end on a hopeful note. What gives you hope, even when fewer young people are taking up weaving? Do you still see a future for this tradition?

Olamide Latifat: To the weavers, I always say this: you’re not just making fabric; you’re weaving history, purpose, and resilience. Your hands are telling stories. Even when you’re exhausted, you keep going. Without you, there’s no tradition. And without tradition, there’s no future. Your work matters. Maybe one day, the world will know your names.

FAB: What do you want a little girl to feel when she watches her mother working with Aṣọ-Oke, just like you watched yours?

Olamide Latifat: I want her to recognize that she’s witnessing greatness. That the strength, skill, and grace she sees in her mother represent a living legacy. And I want her to understand that tradition isn’t outdated; it’s a treasure. It’s gold.

FAB: Metallic or cotton AsoOke?

Olamide Latifat: Cotton.

FAB: Market runs or runway showcase?

Olamide Latifat: Runway

FAB: Red, white, or royal blue?

Olamide Latifat: Royal blue every day, any day, any time.

FAB: Bridal Aṣọ-Oke or festival Aṣọ-Oke?

Olamide Latifat: Bridal Aṣọ-Oke every day, any day, any time.

FAB: If Aṣọ-Oke were a song, what genre would it be?

Olamide Latifat: Afrobeat

Olamide Latifat: Absolutely. We’ve just launched a new collection, and we recently introduced the Vivo Pop Collection. In that line, we reimagined the classic Etu fabric and transformed it into modern corset tops. One piece in particular is called Efunsetan Aniwura, inspired by the legendary Yoruba queen. Through our ready-to-wear collection, we want to tell women everywhere: You are powerful. Don’t be afraid to walk into rooms that once shut you out.

Fun Zone: #FABFastFive

FAB: What movie makes you laugh even after watching it several times?

Olamide Latifat: The Hangover. It was a comedy about a wild bachelor party.

FAB: If you could only listen to one song for the rest of your life, what would it be?

Olamide Latifat: It would be Questions by Asa.

FAB: What food should taste better than its appearance?

Olamide Latifat: Jollof rice should taste better.

FAB: Which would be the smartest animal if they could all talk?

Olamide Latifat: The dog would be the smartest, not the cat.

FAB: What is the certain product you couldn’t live without? That product that you would always find with you?

Olamide Latifat: My lip gloss.